Concentration Cemeteries

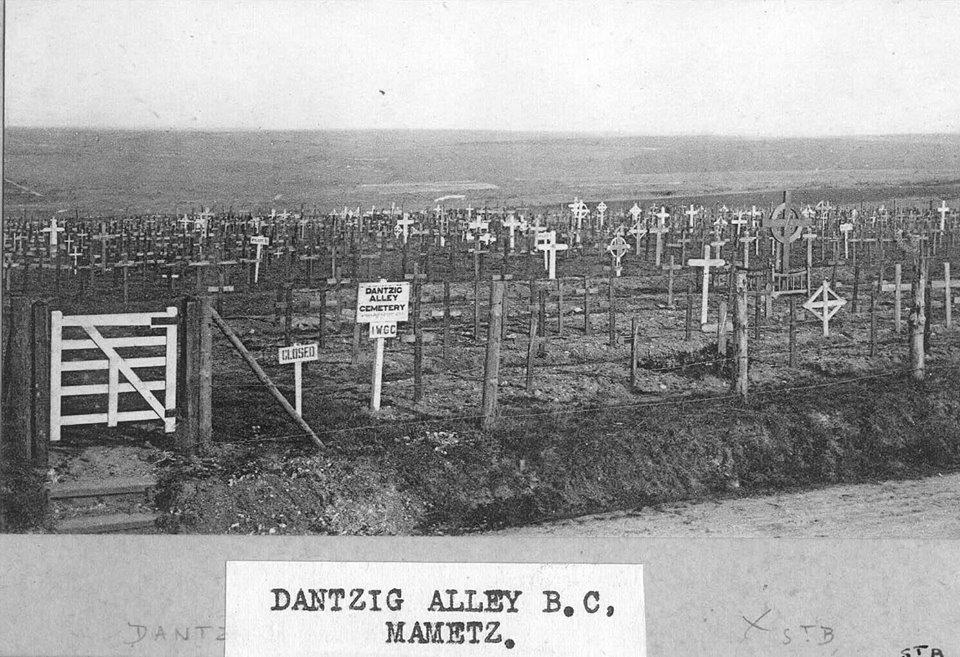

Standing on the ridge of the chalk escarpment leading from the village of Mametz to Montauban, lies the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) Cemetery of Dantzig Alley (Featured Image Courtesy CWGC). 1,535 casualties are commemorated at Dantzig Alley British Cemetery, from a plethora of Regiments and Corps.

There are one hundred and ninety eight members of the Manchester Regiment who are recorded as casualties on 1st July 1916 and commemorated at Dantzig Alley[1]. This focus of Manchester casualties has drawn attention on a number of visits to the area and justified further research.

One may initially assume that the Mancunians fought and died together, but this is not the case. Many members of the 21st and 22nd Battalions were killed in the immediate vicinity of Mametz and the former German Trench they captured at Dantzig Alley. However, the majority of casualties were further afield and represented active service members of 16th, 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Battalions[2]. These seven Battalions formed part of the 7th and 30th Divisions of the Fourth Army, as constituent members of 21st, 22nd, 90th and 91st Brigades; which all had different objectives on the First Day of the Battle of the Somme. These pages are specifically concerned with the 17th Battalion and 90th Brigade, although the men of 19th Battalion, as part of 21st Brigade, are also addressed.

In some locations, casualties remain buried in their original grave plots. For example Devonshire Cemetery near Fricourt, where there is a fitting memorial inscription “The Devonshires held this trench, the Devonshires hold it still.” This was not the case with 90th Brigade.

A large group of 90th Brigade men were originally buried in La Place, Montauban; shown within the tree lined area just beyond the point of the rebuilt church spire. Courtesy http://jeremybanning.co.uk/

The village of Montauban was described as a stinking heap when 90th Brigade made their way through the German positions. Just one of their recognised original burials remains on the battlefield area. This is because the area was reinstated to farmland after the war. See Montauban & Maricourt Photographs then and now. Trenches were filled in, dugouts blocked up and gradually the French people resumed their lives on the hard fought Picardy hills. The light railway was rebuilt cutting through the line of assault and bisecting the principal battlefield cemetery. The buildings, roads and tracks were gradually reconstructed in the 1920s and British graves were relocated elsewhere. There remains little sign of events a century later, yet two hundred and fifty six Manchester Pals[3] are interred in the area from 1st & 2nd July 1916.

© Jeremy Gordon-Smith Interwar Concentration Unit

As time went by other identified burial grounds were relocated and bodies were exhumed when they were identified during reconstruction. Relocations from Montauban continued to London Cemetery, High Wood in the 1950s and isolated remains continue to be found on the Western Front today. The location of the final resting place was determined by the area covered by the particular concentration parties and the time the original burials were found. Most graves for 90th Brigade were relocated in 1919, yet later burials were found in areas that had previously been cleared. It will be seen these men were then reburied in other cemeteries which were being used for current concentrations.

Peronne Road Cemetery. IWM Q78626. Hill 122 War Cemetery at Maricourt. 8-November-1917.

Known graves for men from 90th Brigade have been concentrated to CWGC locations near the villages of Mametz (1919), Bray (1924), Cerisy (1924), Flers (1925), Serre (1928) and Longueval (1928). Much closer are the concentrations of groups of 90th Brigade casualties in Quarry Cemetery, Montauban (1919) and Peronne Road, Maricourt (1916-20). It is hoped that the analysis of the original battlefield graves will provide some assistance for interpretation of other casualties.

IWM Q78627 . Maricourt Military Cemetery was concentrated to Cerisy-Gailly in 1924. The French started the burial plot and named it after Caudron Farm. Photo 8th November 1917

It must be acknowledged that a period up to twelve years was common before some burials were exhumed and bodies were still found in later decades. The passage of time made it increasingly difficult to identify bodies. E.A.S. Gell wrote in May 1921 that the Department of Grave Registration and Enquiries (DGR&E) were only undertaking exhumations for identification “when they had the time. Although 600 bodies a week were being recovered at this time, identification was achieved in only 20% of cases.”[4]. This suggests that concentration parties on the Somme may not have been entirely attentive in their task. It was also acknowledged in 1921 that the concentration parties may have been stood down, despite the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC) noting “Search may usefully be continued” in large areas of the Western Front, including Guillemont and Montauban.[5]

A Grave Registration Unit searching the battlefield for remains c. 1919 Credit. jeremy-gordon-smith-iwm-q91009001

As part of the commemoration of the First World War, the CWGC released records on the re-burials of soldiers in their cemeteries. Data is now available for these Concentration Records, showing the original map reference where men were buried.

CWGC has published incomplete Exhumation Records for the concentration parties. 2nd Lieutenant Robert Calvert of the 17th Manchesters was recovered from Trones Wood in 1929, thirteen years and one day after he was killed on 9th July 1916. It appears his height and pipe permitted identification. These records add amother tier of data, when they can be found.

There can be no doubt the concentration burial parties made efforts to clear burial plots. Farmers then regularly found human remains in their fields in the late 1920’s and dead soldiers on the Western front continue to be found a century later[6]. It is known that there are remains of fifty five men to the east of Talus Bois and there appears to be other likely locations where soldiers were interred. It remains an open question whether efforts should be made to pursue these burials.

Men of the British Army Graves Registration Unit recovering remains from a Western Front battlefield in 1919.

Battlefield Grave Plots

The 90th Brigade suffered more than three hundred deaths in the opening days of the Battle. In the period 1st to 3rd July, more than two thirds of the men who were killed, have no known grave. Less than twenty of the men died of wounds in this period, after being evacuated from the battlefield to Casualty Clearing Stations or other medical facilities. There then remains a relatively small sample of fifty nine (23 from 17th Battalion) men who were originally buried in the area of Montauban and Maricourt.

With the pockmarked ground of the battlefield being captured and retained, there may be a clearer picture on casualties, compared with many areas of the fifteen mile front. In most other locations, advances were not as extensive and gains were not generally held. In these other places burial parties did not have the same unfettered access to collect their comrades and place them in a battlefield grave.

The records of the battlefield graves provide some illustration of the place and timing of the man’s death. This is supplemented by published records, journals and press reports. As a result a wider matrix of information can be developed. It is this group that is addressed to see if any further information can be assessed for the men commemorated at Thiepval.

The theme of lost graves, due to enemy artillery, provides one clear explanation for the extent of lost burials in the Great War. It will be seen that almost half the burials at Vernon Street Cemetery were lost to enemy action before the graves were relocated in 1919. Other small cemeteries in the area will also have been pulverised by the German artillery’s response and counter-attack on the area in the coming days and weeks.

Men from 90th Brigade and other Regiments returned to Montauban after a few days rest and further consideration is given to the work of Burial Parties below. Subsequent bombardments will have continued impact on their efforts. Records show that burial parties removed one identity disk from the men and left the other on the body[7]. In this context, we may imagine the ferocity of the German artillery on the area was part of the reason for so many known graves to be lost.

Anecdotally it seems the impact of enemy artillery fire on battlefield graves was greatest to the north and east of the battlefield. These areas were nearer to the German artillery and more likely to have been under observation from enemy positions, or targeted as assembly areas for later action. Despite this hypothesis, graves were lost in Peronne Road Cemetery, including Private 245941 Murray Simpson MM of 18th KLR and 25 other men. After Montauban had been liberated, the nearest artillery would have been more than two miles distant.

Later concentration records are often the most informative on the reality faced by the men involved and the reality of war for the dead Manchester Pals and Royal Scots Fusiliers. Clear details show the casualties with missing heads, torsos and limbs. The context of violent death cannot be sanitised by the passage of time. Equally, the impact of artillery fire on individuals and their remains is a heavy reminder why so many men could not be identified after the battle and even less, when reburials took place.

Burial Parties

Burial Party near Maricourt 11th August 1916 IWM Q1137

Records and reports of burial parties and Grave Registration Units on the Somme have been addressed. These assist with consideration of the grave location in relation to the possible position where men fell. The gruesome work of the burial parties is not widely reported, but first-hand accounts show the deep and lasting impression this work made on men serving on the Somme.

Sir Fabian Ware took responsibility for the British Red Cross parties charged with recording graves and later became the principal figure in the Directorate of Grave Registration and Enquiries (DGR&E), which is now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). Sir Fabian had limited resources and during 1916, his Grave Registration Units relied on the Army to undertake burials, with the GRUs, solely marking and recording the plots. The public call for knowledge of their lost men became increasingly important through the period of hostilities, particularly when Kitchener’s New Army entered the fray in the Battle of the Somme. For more details of the development of Sir Fabian’s work, see Peter Hodkinson’s excellent article at http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/burial-clearance-and-burial/

Commentators recounted the haphazard nature of the burial parties and prospect that some 90th Brigade bodies may have remained unburied due to the commitments of troops and ongoing battle. Fabian Ware recounted in 1917:-

“At the beginning of the Somme offensive last year I called at the Fourth Army HQ and saw Gen Hutton with regard to this question of burials. There was no organisation for the purpose of the time and I was satisfied after having discussed the matter with them that it was impossible to establish any proper organisation at that time in the middle of severe fighting. Subsequently the organisation of Corps Burial Officers was established.” [8]

© IWM (Q 4023) Making a cross, to mark a soldiers grave. Carnoy Valley, July 1916.

Gunner T P Brennan of the RFA recounted[9] the scene of the battlefield clearance

“Everywhere there was bodies…I saw them burying hundreds of men. They’d dug a hole as big as a room, and thrown the bodies in, crossing bodies. They had to have masks because of the smell was terrible!…”

Private Albert Andrews[10]of 19th Manchesters provided a vivid description as part of a burial party at Montauban.

“On the Monday [3rd July] I was put with others burying the dead and this was when we realised the cost of our victory… Burying your own lads is not a job I want again, some seeming by their looks to have died very easy, others very hard. Some we had to dig out – they had been half buried. The job consisted of getting hold of them, taking their equipment off and emptying their pockets. You put the contents in a gas helmet satchel and hand this to the Officer who is with you giving the man’s name, number and Regiment if possible. Then they are put into a hole ready dug with boots and everything on. You put in about 10 or 15, whatever the grave will hold, throw about two feet of earth on them and stick a wooden cross on the top which is marked by the Officers. For some it was the third day and you could hardly stand the stench as you got hold of them, often having to put them down, go out of the way and have a smoke. The game wanted sticking!”

Lyn Macdonald’s book, Somme[11] provides further first-hand accounts of the burial parties from 13th (Service) Battalion Rifle Brigade clearing the 1st July battlefield near La Boiselle, one week after the 34th Division advance. Lyn recounted the story of a Staff Captain visiting the area and mistaking the blackened corpses of the decomposing British soldiers as Colonial troops. The area of La Boiselle was similar the Montauban battlefield in respect that the advance had been made and held on 1st July. The vivid descriptions from Lyn’s interviews with Rifle Brigade veterans describing the battlefield burials, help understand the burial parties’ work. Corporal Joe Hoyles recounted.

“There was a terrific smell…A smell of rotten flesh…they were seven and eight deep and they had all gone black…Wicked it was! Colonel Pinney got hold of some stretchers and our job was to put the bodies and, with a man at each end, we threw them into the crater…”

If this description was not as reverent as may have been expected, there were clear efforts to ensure the men buried in the mass graves were properly recorded. Sergeant Jack Cross MM recounted

“My job was to take the identity discs off the men. Other people were detailed off to collect the rifles and other people collected the equipment and…stretcher bearers who picked up these dead gentlemen and took them to…this crater and tipped them over…and they buried themselves in the chalk before they got to the bottom.”

The following images remind us of the reality of infantry warfare, possibly sanitised by the censor to avoid showing clearer trauma caused by artillery or machine gun fire. There is evidence the burial parties were unable to identify some casualties, due the terrible nature of their deaths. Remembering friend and foe. Courtesy IWM

Part of the reason for the more informal approach to the burials was the threat to the Rifle Brigade men from the ongoing German bombardment of the area, with at least two casualties recorded for the 13th Battalion.[12] The scene of the continual threat and pulverising impact from artillery will have been equivalent. There will also have been similar problems for the identification of dead men held on the former German lines . Acting Corporal Ruper Weeber recounted the impact of the continuing carnage for the dead members of the 34th Division.

“ Some were without legs, some were legs without bodies, arms without bodies. A terrible sight…It made me wonder what it was all about.”

With reports of numerous losses of the 90th Brigade men defending Montauban after the attack, it is a little surprising that there are so few burial plots identified after the battle. The 18th Manchesters returned to bury the dead on 4th – 7th July, helped by the 16th Battalion on 5th July, the 2nd RSF on 6th & 7th July and 11th Battalion Royal Scots providing burial parties the next day.

IWM Q 65447 Men of the Middlesex Regiment (Probably 12th Bttn of 54th Brigade) preparing graves for German dead. Between Montauban and Carnoy. July, 1916. Possibly Talus Bois German Cemetery Extension in Railway Valley

Records show men went back to the specific place where they knew their friends had fallen, yet no trace could be found; and the individual’s resting place still remains unknown. This suggests that the men may have already been buried and that such grave has been lost. Otherwise the continual bombardment of the British line in front of Montauban may have removed all trace of the lost men.

Captain Morton Johnson (16th MR) had been seen handing up ammunition to the machine gunners at Montauban Alley when he was killed. Lieutenant Nash returned to bury his friend and no trace could be found.[13]

Press reports indicate Lance Corporal 6654 Henry James Milsom and Private 6709 James Yates (both 16th MR) were buried by the padre near where they fell. Reverend Robert Balleine probably gave his blessing to a large number of mass burials and these particular graves were lost.[14] It is interesting to see confirmation that the burial party found suitable plots close to where the men fell, but sad that the grave markers were possibly lost and the men remain interred somewhere on the battlefield. Otherwise, the actual burial plot may have been obliterated by subsequent bombardments.[15]

Sergeant Bert Payne (16th MR) met Rev Balleine, the Brigade Padre, on his way to the rear after being wounded in the face during the final assault. Rev Balleine had been attending the wounded with the Battalion Medical Officer. Bert recounted that Rev Balleine then made his way to the rear and must have later returned to assist the burial parties.

Body density map (blue) of recorded burials in each grid square compiled by the Grave Registration Unit in 1916/17. Burials in the identified cemeteries (red) are excluded from the figures.

Reviewing 90th Brigade casualties

The CWGC records provide a grid reference of the position of the original burials. These identify an accurate geographical position to a grid point that is fifty yards square. For further explanation, the Western Front Association has provided an excellent guide ‘How to find a point on a Great War trench map’. This can be combined by a tool to quickly find the point of an original burial on modern maps Great War British Trench Maps Coordinate Convertor and the plotting of graves with original trench maps as overlays can be made on the National Library of Scotland archive Map images – National Library of Scotland. McMaster University Library provides further trench maps for reference purposes.

The men of 90th Brigade advanced from Maricourt at 08.30 on 1st July and retired from Montauban in the night of 2nd / 3rd July. There are a series of times and places where casualties will have taken place:-

- During, or prior to the initial advance from Cambridge Copse, past Machine Gun Wood and up to the line held by 21st

- Passing through the British and German lines to Glatz Redoubt and Railway Valley where they waited for the barrage to lift.

- The final assault on the village at 10.05 on 1st July and subsequent transporting of equipment and resources from the reserve lines to the newly held defences.

- Retiring wounded through the scenes of their advance and falling before reaching successful medical aid.

- Up to thirty six hours of sniper and machine gun fire with sustained artillery fire on weak defensive positions and repelling two attempted counter-attacks.

The combination of Concentration Records and Trench maps provide some illustration of the possible location of losses. In some instances, anecdotal evidence provides further indication of the particular time or place for the men concerned. Credit can be given to numerous sources of information, notably The Manchester Regiment Forum and John Hartley’s History of the 17th Manchesters. Press reports have also been addressed.

A significant challenge is created by contradictions in evidence, for dates (1st or 2nd July) or cause of death (killed in action of died of wounds). More directly, the overlap of possible locations is generally impossible to judge between men falling in the initial advance and those who were killed, or died, on their return from Montauban. In the group of men with known graves, there are some instances where reports confirm the man had fallen on the battlefield on his return from Montauban.

The Thiepval Memorial also commemorates a group of men who were wounded and died on their way back towards Maricourt. Lance Corporal 10779 Arthur Frederick Hammond of D Company (18th MR) from Ardwick, had been wounded by machine gun fire and was been carried to the rear when he was killed by a shell.[1] Corporal 9932 George Baldwin Shepley (18th MR) had been wounded in the wrist and killed on the way to the dressing station. Corporal 6503 Rowland Hill (16th MR) had been shot through the mouth or throat and was last seen making his way to the rear. He was buried close to where he fell.

It is not always possible to be sure where the men were wounded and even more difficult to suggest where the men fell, or why they have no known grave. The 19th Battalion Manchester Regiment War Diary provides Orders that stretcher bearers should use the railway track (to the west of Talus Bois) to transfer casualties to the Dressing Station. However, if 90th Brigade bearers used the same route, there is still no certainty they had reached Talus Bois when the men had been killed.

This challenge illustrates the importance of the analysis of the actual burial locations for the Brigade. For a logical progression of the review of the battlefield graves, we start in the rear positions, behind Brigade assembly positions at Cambridge Copse. Progressive steps are then made to Montauban and the advance positions beyond the village.

Burials to the rear of assembly trenches

[1] MEN 24/7/1916.

[1] This includes 6 men commemorated at Dantzig Alley, with lost graves at Vernon Street.

[2] CWGC records also identify men from 4th, 14th, 25th, 26th & 27th Battalions. These were Depot, Training Reserve or Special Reserve Battalions of the Manchester Regiment, from which men had been posted or attached to the active Battalions that are listed. There are also later burials from 11th and 12th Battalions.

[3] This includes the 19th Bttn of 21st Brigade to be a total of lost burials for the 1st, 2nd, 3rd & 4th Manchester Pals. Some of these men will hold Unknown graves in cemeteries

[4] http://www.vlib.us/wwi/resources/clearingthedead.html

[5] http://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/burial-clearance-and-burial/

[6] http://www.cwgc.org/news-events/news/2016/10/marmon-carter-reburials.aspx

[7] http://www.vlib.us/wwi/resources/clearingthedead.html

[8] F. Ware to DGR&E, CWGC SDC 60/1 Box 2033.

[9] Also Maddocks

[10] Orders are Orders-A Manchester Pal on the Somme 1987. Neil Richardson

[11] P 113-114 Penguin 1983. Thoroughly recommended.

[12] Rifleman W. Darling and G E Evans were buried close to Lochnagar Crater and subsequently concentrated to Bapaume Post Military Cemtery, Albert.

[13] Morton Johnson is commemorated at Thiepval.

[14] Both men are commemorated at Thiepval.

[15] Also See Vernon Street Cemetery where more than half the known graves had been lost when the graves were relocated to Dantzig Alley.