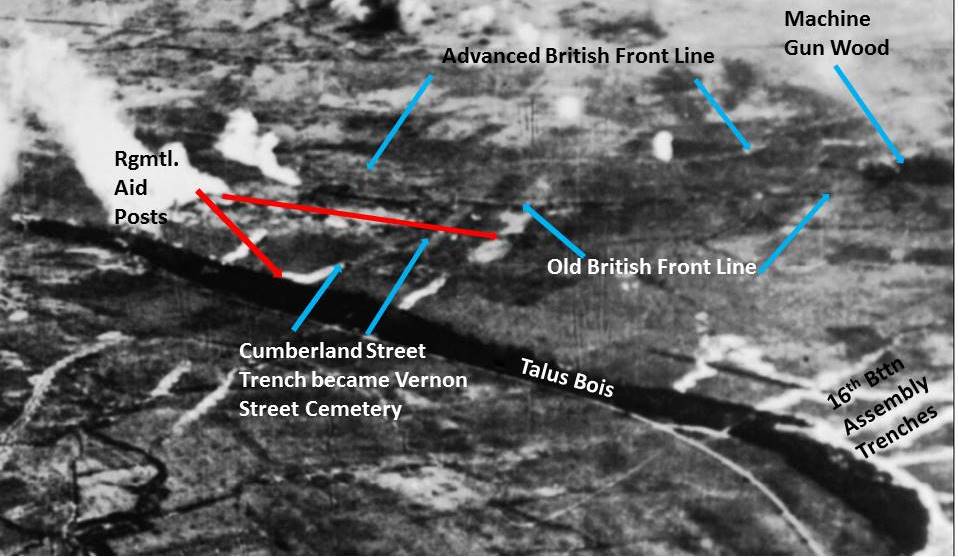

Aerial photo of the area covered in the initial advance. IWM Q55066

Private 8055 Arthur Bell reported one of the earlier casualties for 17th Battalion as the men left their assembly trenches near Cambridge Copse.

Thomas Henry Clesham

“The first casualty I remember was our Platoon officer, we were in artillery formation and he was leading – but I do not think he could have been sniped, unless by some very clever German trickery. Anyhow, he just go it in the head with one leg off the ground, and must have died that instant.”

Further accounts indicate this was 2nd Lieutenant Thomas Henry Clesham, who must have been killed towards the centre of Grid 62C.A.15.a and his body was not identified if it was later recovered. It is possible Thomas may be an Unknown Soldier, buried in Talus Bois Cemetery, along the track to Carnoy.

The 17th Battalion Commanding Officer was wounded near the British front line and handed over Command to Major MacDonald. There must have been many other casualties as the Battalion presented themselves to the German artillery, snipers and machine gunners.

Private 7358 Joseph W Forgham (16th MR) was killed by machine gun fire while advancing. Lance Corporal 7272 Samuel Ravenscroft (16th MR) suffered the same fate, leading his Section in file. In common with Thomas Clesham and numerous men of 90th Brigade, Joseph and Samuel have no known graves.

Grid 62C.A.9.d – Machine Gun Wood

2nd Lieutenant T A H Nash [1](16th MR) recounted casualties as the Brigade passed the British and German front line.

“We had to cross our own front line trenches and those of the Germans…These trenches were full of dead and wounded, ours and the Germans.”

Manchester Evening News 8/7/16. Thanks to Atherton of MRF

Capt. N.Vaudrey. O.C. B Coy.

Many of these causalities will have been members of 21st Brigade, with some further losses from 90th Brigade as they succumbed to artillery and machine gun fire. The 17th Battalion advanced to the British front line with their eastern flank close to Machine Gun Wood. Captain Norman Vaudrey, the Officer in Command of B Company , was buried in the original British front line trench, although evidence shows he was killed much further forward, near Glatz Redoubt.

A letter from Major Whitehead recounted

“… the 16th and 17th Battalions were in the firing line, and having passed over the German trenches were advancing…when the first Company (‘A’ Company) was momentarily held up. Captain Vaudrey, commanding the second Company, went forward to ascertain the cause of the halt in advance when he was hit in the stomach by a bullet from a German machine gun, and died in 30 seconds in the arms of a Sergeant …”

Lieutenant J. C. Wilson of The King’s Own Scottish Borderers also wrote to Norman’s parents:-

“After the battle a few days ago, I found the body of Captain Vaudrey in our trench, and I had him properly buried. I found an envelope with your address by his side. There were no other personal effects on his body…By our trench, I mean the captured German trench”[2]

The German front line was more than 500 yards in advance of Captain Vaudrey’s original burial and this example shows that battlefield burials may have been some distance from the place where casualties were originally found. In principal, it can still be seen that Captain Vaudrey was killed in the first phase of the assault, leaving similar assumptions in place, that the Battlefield graves provide some limited indication to the point where men fell.

It is noted that Captain Vaudrey’s grave was slightly downhill from the German front line, supporting the hypothesis that early burial parties did not usually carry their dead comrades up hill. The evidence also suggests that Officers may have been treated differently to Other Ranks. Numerous men from 17th Battalion will have fallen at in the network of trenches that had been passed before Captain Vaudrey was killed. In the context that only a small proportion of casualties have known graves from the battlefield, it seems possible that burial parties just back filled the former German defences where they lay. Otherwise Captain Vaudrey would have been treated this way, rather than receiving a ‘proper burial’. He is now interred at Dantzig Alley.

Sergeant 7185 Joseph Payne (2nd RSF), a former Reservist from Birmingham and 17th Battalion’s Private 27321 Charles Robert Felstead, from Ancoats is buried in a similar position and it is assumed they were also killed in the initial advance to Glatz Redoubt. Private 12357 William Hamilton (2nd RSF), from Kilbirnie, Ayrshire, was buried alongside Joseph Payne, although he is recorded in SDGW as dying on 2nd July. It may be assumed he succumbed to wounds close by, possibly remaining in this position from the initial assault, or on the return from Montauban, after the successful attack.

Grid 62C.A.9.c – Squeak Forward Position / Vernon Street Cemetery

Towards the west side of the 90th Brigade advance, there were significant casualties from enfilade fire from a German post at The Warren. This had not been dislodged by 55th Brigade, which had been stalled in their advance on the other side of Talus Bois. This was reported to the widow of Private 7465 Richard Hughes (16th MR) by his OC, Lieutenant Jackson “We were advancing in the open under fire when your husband was shot through the heart by a machine-gun on our left.” It is anticipated Richard Hughes may have been buried in the area of Vernon Street, or further south along Talus Bois.

One clear example of the work of the burial parties is presented by the photograph of the board marking the graves in the late Graham Maddocks’ excellent book “The Liverpool Pals”.

Squeak Forward Position Memorial Board. Photo Credit the late Graham Maddocks – Liverpool Pals. Pen & Sword ISBN: 9781473816015

The concentration records for the named men identify the grid position immediately to the east of Talus Bois, behind the original British front line at Queen Victoria Street. The Board included the names of Private 7632 Arthur Clay from Middleton and Lance Corporal 6527 William Mein MM[3] ( both 16th MR) from Stockport, together with Glaswegian, Private 20648 William Bell (2nd RSF)

These men were buried in the location of a former reserve or assembly trench, known as Cumberland Street. A Regimental Aid Post was at the eastern end of this trench and another aid post was one hundred yards to the south at the junction of a reserve trench and a new communication trench constructed from the advanced front line; and constructed for the evacuation of the wounded. The men are recorded as sharing this position with seven members of the 18th KLR and nine casualties from the 2nd Yorks. 4 Company of the 18th Battalion KLR used the Cumberland Street as an assembly trench prior to the advance. It is notable that some of these men still hold the assembly trench today (See Devonshire Cemetery Fricourt).

Private 26388 Nelson Arthur Pullen was buried 500 yards to the south of the group, according to the concentration record. However inaccuracies are known in the sheets (see below), which indicate Nelson Pullen may also have been buried near squak forward position, particularly as he was re-buried in the same row at Dantzig Alley with some of the KLR men mentioned on the Board.[4]

Courtesy Northern Bank Memorials

Lt James Watson’s Family Memorial in Londonderry. Courtesy Trevor Temple

Lieutenant James Watson of 27th Manchesters (attached 17th Battalion) was killed at Guillemont on the night of 29/30th July 1916. He was buried with the earlier July casualties in the reserve trench[5]. Lieutenant Watson’s family Memorial and is Service Record shows James was buried at Squeak Forward Position, Carnoy. CWGC records show this burial plot became known as Vernon Street Cemetery. Vernon Street is identified on the Body Density plans at the junction of the reserve trench and British front line and it seems probable that the cemetery extended along the reserve trench towards Talus Bois.

Lt James Watson XII Pln 23rd Bttn

Lt James Watson 1916 Credit Bury Grammar School.1

Vernon Street was actually a front line trench, running parallel with the reserve trench, 100 yards to the north. One assumes this provided a more appropriate name than Squeak Forward Cemetery. Both Vernon Street and Cumberland Street are roads in Liverpool City Centre and the trench names probably followed these examples, named by the 21st or 89th Brigade men who garrisoned this line in the preceding months. Another communication trench in the area was known as Trotter Street, presumably after the 18th KLR’s Commanding Officer. James had previously been OC of XII Platoon of 23rd Battalion. He had suffered appendicitis in 1915, posted to 27th Battalion, when the 23rd had left for France.

CWGC records indicate there were initially one hundred and ten burials at Vernon Street, including some 90th Brigade casualties from later dates in July.

We must also taste a harsh reality that the Battle of the Somme lasted one hundred and forty one days. With continuing enemy bombardment, many graves were lost and some casualties were lost before burial. Following the failure of the advance further north, the Generals focussed future assaults in the southern area. 90th Brigade and numerous other Divisions pressed forward to the infamous positions at High Wood, Trones Wood and Delville Wood. Less than two miles to the east of Montauban was the fortress village of Guillemont, which was fought over by numerous British soldiers until it eventually fell three months later.

During this period, Montauban became a major stronghold for Britain and Commonwealth forces. The German artillery commanders were entirely familiar with the co-ordinates of their former defences and had heavy artillery was targeted on the area, from compass points to the north west, round to the north and east.

The area was repeatedly ravaged by artillery barrage, including the support areas, such as Vernon Street. The burial parties had made great efforts to bury the dead from the battle, but many graves were lost and the statistics for men commemorated at Thipeval confirms that many bodies must have become unrecognisable or lost in the broken ground.

Vernon Street was a sensible place for burials, being hidden from the German observers view by the relief of the land. However, the artillery barrage took its toll on the cemetery during later days and weeks. CWGC identifies fifty five men whose graves were lost at Vernon Street, who are now commemorated on the Dantzig Alley Memorial, with individual commemorative headstones lined along the back wall of Dantzig Alley Cemetery.

MEN 15/7/1916

There are three 1st July of 16th Battalion casualties commemorated on the Vernon Street Memorial. They are Privates 6598 EF Dakin of Brook’s Bar, Private 6856 James Frederick Davies from Moss Side and 18 year old Private 27115 Frank Fielding from Marsden[6] (16th MR), who was killed at the beginning of the assault. Other members of 90th Brigade are Derby Scheme man, Private 27357 Robert (Bob) Gordon Brown, from Levenshulme and 10409 Harry Howard of C Company (both 18th MR), from Withington. 7653 Private Frederick Gibson from Cheetham Hill, is identified as a 19th Battalion casualty at Vernon Street by CWGC, although his number and Grave Registration refers to 16th Battalion. Frederick’s Regimental Number is also consistent with 16th Battalion. There is every expectation these men were cut down by machine gun fire from The Warren before they were buried in Vernon Street Cemetery. Photos of the commemorative headstones are below. Some images credit Manchester Regiment forum

With one hundred and ten known burials in Vernon Street Cemetery and the attrition of shellfire, representing the loss of half of the graves is significant information. The sign board photographed near Talus Bois provides an indication of the possible source for the roll of names at Vernon Street. It is anticipated the burial parties or Grave Registration Unit constructed this sign board and painted their comrades names on it. It would then seem feasible that further sign boards were produced at Vernon Street. These may have provided the schedule of names used to identify the lost graves commemorated on the Dantzig Alley Memorial.

The German artillery may well have shelled the area of the former British front line in the days after the assault. It is more likely the German guns targeted the newly advanced positions in the village and beyond in Montauban Alley. In this context there is no surprise that so few graves were identified in the village when a significantly greater proportion than fifty percent are likely to have been lost.

Many burial parties on the Montauban ridge will have been observed by German artillery and graves may not have been quite so well constructed compared with the more benign positions to the rear. It is also likely a larger proportion of casualties in the village will have had less formal graves, bodies will have been unrecognisable or markers were lost.

An early hypothesis arose that the number of known graves in a particular part of the battlefield could indicate the number of casualties in that general area. It is now thought to be equally likely that the number of known graves is connected with the extent of subsequent bombardment in an area. Other factors were also relevant including the anticipated downhill journeys for burial parties and safer positions away from the view of German observation.

It will be seen there were battlefield cemeteries in Railway Valley and Montauban. The presence of burial plots in more advanced positions indicates that those men were killed in later stages of the assault. The men buried in Vernon Street are therefore expected to have been killed in the initial advance between 08.30 and 09.30; after which the Brigade paused in Railway Valley before their final rush on the village. This hypothesis is supported by the evidence that the majority of Vernon Street casualties served in 21st Brigade, which did not generally advance beyond the southern slope overlooking Railway Valley.

Tom Mounsey of 18th KLR. Vernon Street Memorial http://www.roydenhistory.co.uk/eportwarmemorial/

CWGC records indicate burials were carried out at Vernon Street by 21st Brigade. Twenty seven members of the 2nd Battalion Yorkshire Regiment were buried in the area of Vernon Street Cemetery and only nine graves could be identified in 1919. The names of all these men are shown on the Memorial Board. Similarly twenty nine members of 18th Battalion King’s Liverpool Regiment were buried in the area and twenty one could not be identified when burials were concentrated to Dantzig Alley. Seven of the known graves represent men shown on the Memorial Board.

There were no other casualties from the 19th Battalion identified and concentrated at Dantzig Alley. These men had been on the eastern side of the advance and their burials must have been on the other side of the front to the assault. The 17th Battalion followed part of their City comrades’ path. This explanation assists in finding why there were no known men from the Battalion identified at Vernon Street, yet there were a small group from 16th Battalion, which was on the western side of the assault, close to Vernon Street. The position of the British and German trenches was diagonal to 90th Brigades line of attack. The absence of 17th Battalion graves at Vernon Street builds an assumption that burial parties started collecting casualties nearest to each burial plot.

The members of 21st Brigade that formed the burial parties will have been committed to the western side of the battlefield, without time or resources to extend their work to the eastern side of the assault where 17th and 19th Manchesters had fallen.

Apart from the limited burials near machine gun wood, it seems likely that many members of the 17th Battalion had less prepared burials, possibly where they fell. The Body Density map for the sub-Grid Square 9.d identifies thirty nine registered burials directly to the east of Vernon Street. Three of this group have been introduced from 90th Brigade and three others have been identified from 21st Brigade. There will have been few later casualties in the area, which became support lines. As such it is likely there may have been a group of 17th, 18th, 19th Manchesters or 2nd RSF who had registered burials, but could not be found or identified when the Concentration parties carried out their task after hostilities. Thirty four burials in the two sub-grid squares directly to the south may account for some of the earliest 90th Brigade casualties, close to their assembly positions. Few have been identified.

[1] The Diary of an Unprofessional Soldier edited by TAM Nash. Picton 1991

[2] The Buxton Advertiser – 15 July 1916

[3] Military Medal awarded for action on1st July. LG 19/2/1917.

[4] A later group of burials may have been made in the Reserve Trench, even though the concentration report indicates reference c.6.1, rather than c.6.7. This includes members of the 17th MR and 2nd RSF. 18th KLR men shown on the photo of the Board identify individuals with concentration records as 6.7.

[5] Incorrect grid reference on Concentration Schedule as 6.1, rather than 6.7, confirming transcription error.

[6] Frank Fielding “…was killed in action at the beginning of the great advance. His Captain wrote: “He died instantaneously whilst we were going forward…” Private Fielding was but 18 years old and before joining the Manchester Pals on May 7th he was an assistant to Mr S T Shaw, Chemist, Peel Street, Marsden.’ Huddersfield Daily Examiner 21 July 1916.